Estorick Collection & Anglo-Italian: Rationalism on Set

It has been a real pleasure working with curator Roberta Cremoncini. A Florence native who has been at the collection for over 25 years, Roberta consistently devises a fascinating and diverse program that spans modern Italian art, design and culture. Following every visit to the collection's Islington home, we are always struck by the close parallels between our influences and the exhibitions found within.

Looking through the archives from the last decade there are a plethora of fantastic exhibitions which we would like to share with our community. Thanks to the team's generosity we are pleased to republish a handful of our favourites online for the first time.

We hope you enjoy this inaugural edition:

Rationalism on Set: Glamour and Modernity in 1930s Italian Cinema (2018)

Carlo Levi and Enrico Paulucci, Set design for Patatrac, (Dir. Gennaro Righelli, 1931), Gelatin silver print on paper, 17x23cm, Collezione Museo Nazionale del Cinema, Turin

Italian cinema of the 1930s is often dismissed as a minor phase in the history of the medium, represented either by frivolous romantic comedies or propaganda exercises for the Fascist regime. The aim of this exhibition was not to discuss or to re-evaluate the merits of these films per se, but to examine the contribution made by a significant number of the productions dating from this period to the development of a new, Modernist aesthetic in set design.

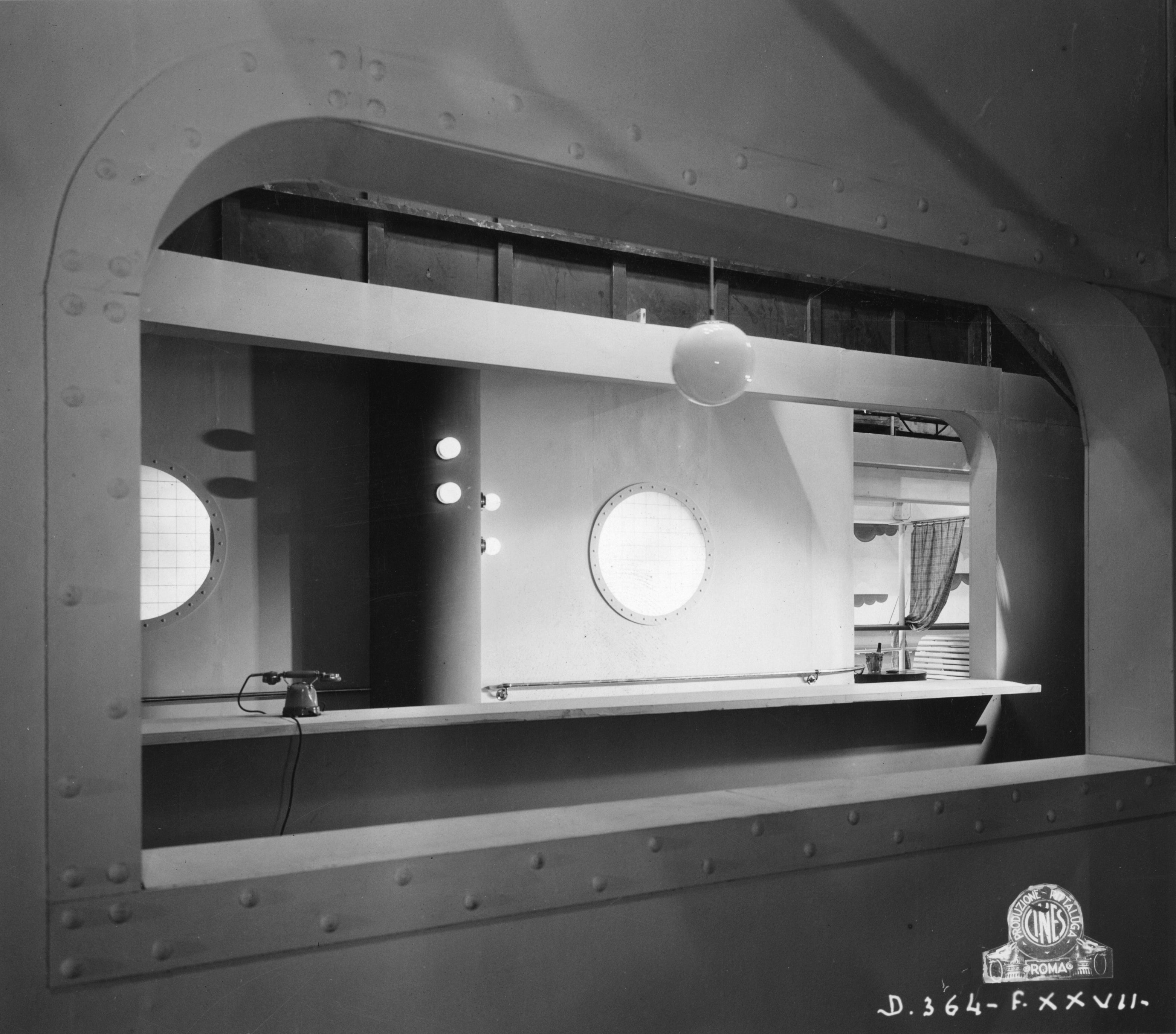

Gastone Medin, Set design for Due cuori felici, (Two Happy Hearts; Dir. Baldassarre Negroni, 1932), Gelatin silver print on paper, 17 x 23 cm, (Photographer: attributed to Aurelio Pesce), Fondazione Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia – Cineteca Nazionale

Studies on this topic have so far focused mainly on Germany, France and the United States, which undoubtedly produced the most original, even ground-breaking, cinema sets of the first era of Modernism. However, if we look at cinema’s early history, Italy had played a crucial role in this field. In 1914 Giovanni Pastrone’s film Cabiria had revolutionized the way sets were conceived and created. No longer flat backdrops painted with trompe l’oeil architectural elements, such as those used by Georges Méliès, the film’s spectacular three-dimensional sets were constructed on a grand scale and with great attention to detail. Its success convinced producers that investing time and money in constructed sets was the way forward.

Gastone Medin, Set design for L’ultima avventura (The Last Adventure; Dir. Mario Camerini, 1932), Gelatin silver print on paper, 12 x 24.4 cm (Photographer: attributed to Aurelio Pesce), Fondazione Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia – Cineteca Nazionale

A few years later it was the Italian avant-garde that left its mark on the history of film sets, in the form of the strikingly abstract design by Futurist artist Enrico Prampolini for the 1916 film Thaïs by Anton Giulio Bragaglia. This isolated episode represented what is probably the earliest example of Modernist décor in cinema.

The years after the First World War saw France and Germany at the forefront of innovations in set design, especially through the work of directors such as Marcel L’Herbier and Fritz Lang. The German film industry was propelled by the powerful studio UFA, and its modern set designers found a major source of inspiration in the Bauhaus: a new, radical school of design and applied art that was to become hugely influential for European art and architecture. However, the aesthetic of Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece Metropolis was also influenced by other strands of Modernism: set designer Erich Kettelhut’s sketches, in particular, echo the architectural designs of Italian Futurists Antonio Sant’Elia and Virgilio Marchi. As the exhibition illustrated, a Futurist thread can be traced through the history of 1930s Italian cinema, many of whose protagonists also took part in the contemporary international exchange of ideas about art and design. The exhibition explored these reciprocal influences, hoping to provide a starting point for further research into this subject.

Modern Architecture

The 1920s were a momentous period in the history of modern architecture. In the aftermath of the First World War, many European artists and architects were animated by a new spirit of innovation, often accompanied by a sense of idealism and social justice. There was a widespread belief that technology would help progress not only in the economic sphere but also in society as a whole. Largely originating in continental Europe, the Modern Movement was the new architectural current that revolutionized building design by advocating functionality and the clear expression of structure and materials. The wide diffusion of its principles was confirmed by the famous exhibition on the International Style held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1932. Its development was made possible on the one hand by technological advances and the extensive use of concrete and steel structures, and on the other by a decisive rejection of the previous century’s historicism. The adoption of frame structures, as opposed to load-bearing walls, translated into a much greater freedom of internal layout, and in the development of open plan designs. Interiors tended to be uncluttered and populated by furniture that, through its materials and functionality, defined a new, modern aesthetic. One of the main centres of the new architecture was the Bauhaus school in Germany, founded in 1919, whose director Walter Gropius (1883-1969) was one of the key figures of the movement. It also included his compatriot Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969, the last director of the school, which was closed by the Nazis in 1933) and the Swiss-French Le Corbusier (1887-1965). The Bauhaus advocated the unity of art, technology and science; it encouraged teamwork, experimentation and inter-disciplinary approaches, overcoming the distinction between fine and applied art.

Luisa Ferida in a publicity shot for the film L’argine, (The Embankment; Dir. Corrado D’Errico, 1938), Set design by Carlo Enrico Rava and Salvo D’Angelo, Gelatin silver print on paper, 30 x 23.5 cm (Photography: Foto Pesce), Collezione Museo Nazionale del Cinema, Turin

Italian Architecture and Cinema

Meanwhile, there had been little innovation in both Italian architecture and cinema. However, an increasing number of architects were embracing the new continental developments and trying to shake up the architectural establishment. In 1928 a number of modern architects, grouped under the name of MIAR (Italian Movement for Rational Architecture), organized the first exhibition of Rationalist architecture, which was closely affiliated to the Modern Movement. Rationalist architects could, to a certain extent, rely on the favour of the Fascist government – at least during the first half of the 1930s, when the regime attempted to attract the widest possible support base, and therefore allowed a surprising plurality of cultural attitudes and approaches. Several of these architects were also deeply interested in other visual arts, such as painting and cinema, and were in close contact with modern architects in other countries, being well aware of developments taking place in Europe in the fields of architecture, photography and art in general.

Gastone Medin, Set design for Cento di questi giorni (Many Happy Returns; Dir. Augusto and Mario Camerini, 1933), Gelatin silver print on paper, 14.7 x 23.9 cm, Fondazione Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia – Cineteca Nazionale

After the crisis of the early 1920s, caused by a lack of technological progress and an inability to compete with foreign imports, the Italian film industry was starting to show signs of recovery by the end of the decade. The lack of infrastructure was counterbalanced by the wide circulation of ideas and information concerning foreign works, and the interest among intellectuals for avant-garde cinema, and for the medium in general. The young film critic – and later director – Alessandro Blasetti (1900-1987) argued for the renovation of Italian cinema from the pages of his periodical Cinematografo, which also published examples of modern set décor. Most of the illustrations for the magazine were provided by an even younger draughtsman, Gastone Medin (1905-1973), who made his own debut in cinema as set designer for Blasetti’s first film Sole (Sun) of 1929.

Cines

The early 1930s were dominated by Cines: the only studio that acted as both producer and distributor. Originally founded in 1906, it was relaunched in 1929 by Stefano Pittaluga (1887-1931), who had been active in the film industry since 1914. He had the studio’s first soundstages built in 1930 and hired young professionals as part of his attempt to modernize Italian cinema. At the same time, he turned to experienced directors, bringing some of them back from abroad, where they had been working during the 1920s. Pittaluga was exclusive distributor for the films of Universal, Warner Bros and Berlin’s Terra Film, but also aimed at expanding the market for Italian films; to this end, the first films in production under Pittaluga also had international versions, realized with foreign film crews. Despite his early death in 1931, Pittaluga created the premises for the production of a number of films that would become prototypes for the romantic comedies typical of the decade – often inspired by, if not explicit remakes of, foreign productions. Their contemporary settings offered opportunities for set designers with Modernist leanings to create innovative interiors, which featured elements borrowed from the International Style. After Pittaluga’s death, his place at Cines was taken by the art and literary critic Emilio Cecchi (1884-1966) who, equally keen on modernizing Italian cinema, brought in writers and artists with the intention of producing commercially successful films that also had artistic merit. In 1930 Cecchi had taught at the University of California, and during his time there had had the opportunity to familiarize himself with the Hollywood studio system. About one third of Italy’s entire national production between 1930 and 1934 was released by Cines, and its sound stages were also used by other studios.

Carlo Levi and Enrico Paulucci, Set design for Patatrac (Dir. Gennaro Righelli, 1931), Gelatin silver print on paper, 17x23cm, Collezione Museo Nazionale del Cinema, Turin

HollywoodItalian set design of the period also reveals the influence of American film décor. At the beginning of the 1930s Hollywood had represented a business model, with its vertically structured studio system that controlled all phases of production; this was something that Cines aimed to emulate. The popularity of American films with Italian audiences could not be ignored by producers, even as they aspired to create a recognizably national cinematic style. The Hollywood film industry had received an influx of European émigrés – with a significant majority from Germany – who were initially attracted by the artistic and economic possibilities on offer, but increasingly motivated by the need to escape the hostile political climate in Europe. The designers among them exerted a decisive influence on Hollywood set design, especially at Paramount, one of the three major studios (with RKO and Metro Goldwyn-Meyer) to fully embrace Modernism. It could be argued that the influence of modern German design on Italian film architecture also occurred indirectly through Hollywood cinema. However, the most prominent figure in Hollywood set design of the 1930s was MGM’s Cedric Gibbons, whose architecture and engineering department employed some of the most talented designers in the field and was responsible for the largest body of Modernist sets of the time. The studio’s style incorporated Modernist influences ranging from Frank Lloyd Wright to De Stijl, but also distinctly Art Deco elements.

The Later Years

The second half of the 1930s was characterized by a debate between film critics and architects regarding the role of set design, which opposed ‘realistic’ to ‘modern’, ‘imitation’ to ‘interpretation’ and ‘truthfulness’ to creative expression. The architect-set designer Carlo Enrico Rava warned of the danger of utilizing modern elements purely for aesthetic/decorative purposes in the pages of Domus. Guido Fiorini expressed a similar concern in the cinema magazine Bianco e Nero, in which he discussed a recurring type of décor recurrent in Italian films of the time, which could be defined as a sort of ‘eclectic’ Modernism. According to Fiorini, this style gave designers great freedom and allowed them to indulge in Surrealist solutions; however, he deplored that it had been overused, to the point of losing any meaning and becoming a cliché. He exhorted designers to avoid the excesses of what he called the ‘American style’, but at the same time not to lose their creative spirit. These issues, and the film culture that had generated them, were soon after swept away by the reality of the Second World War, and a very different genre of Italian cinema emerged from the aftermath of the conflict.

La Signora di Tutti, 1934, Dir. Max Ophüls

The research in Italian film archives essential to this project was conducted thanks to the RIBA’s Gordon Ricketts Memorial Fund and the Art Fund’s Jonathan Ruffer Curatorial Grant.

The full exhibition catalogue is available to purchase here.